The best way to return to the previous page is the backspace key (above the return key). On Macs this is the 'delete' key.

Or just click on the pictures to get back here.

Andy's Early Comics Archive

Comics from 1783 to 1929

1700-1800 The Birth of Modern Comics Töpffer 1840-1860 Busch 1860-1900 1895 1900-1929 (unidentified 1860-1900)

1800 - 1840 (pre-Töpffer)

The Birth of Modern Comics (1800-1860)

Comics from 1783 to 1929

|

This is a presentation of historical comics, intended to enlighten and amuse students of comics history, (and to provide their teachers with reference material.)

Maybe these early comics will also inspire some of today's comics artists.

Most were scanned by me, ususally from books or magazines lent to me. Sometimes I get sent a dvd with scans someone made from his own collection.

|

1700-1800 The Birth of Modern Comics Töpffer 1840-1860 Busch 1860-1900 1895 1900-1929 (unidentified 1860-1900)

1700 - 1800

|

William Hogarth 'The Harlot's Progress (1730)

small version click here

The famous 'progressions' by Hogarth were not actually comics. The images don't lead into and don't interact with each other. Each shows a distinct, separate stage of a longer story. However, because of their great popularity, they established the very notion of telling entertaining stories with a series of pictures and so became a highly influencial stepping stone for future developments.

|

|

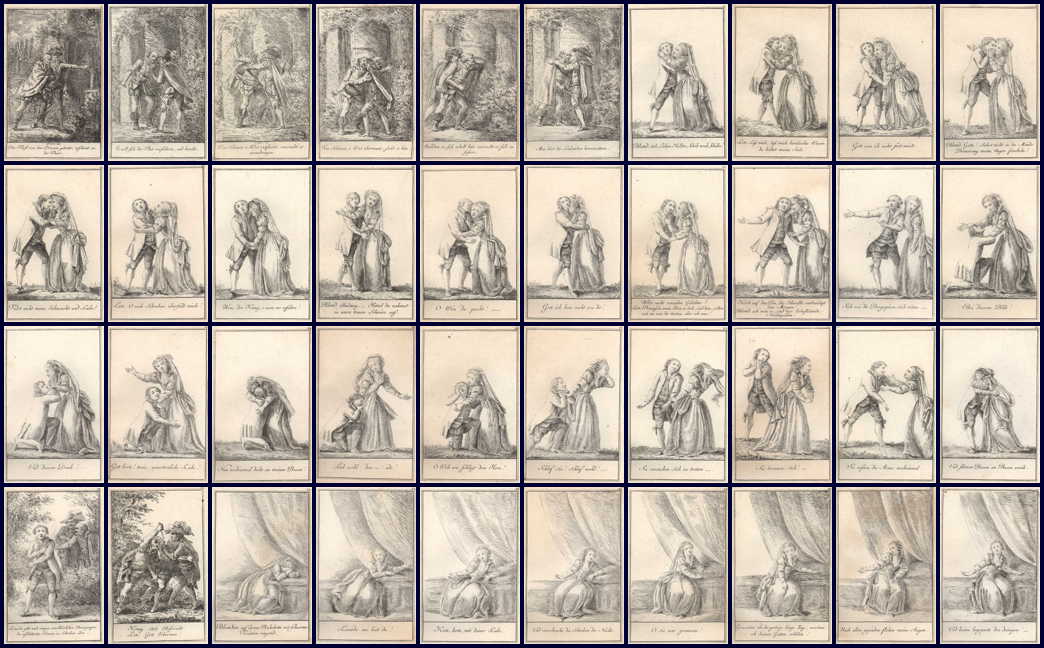

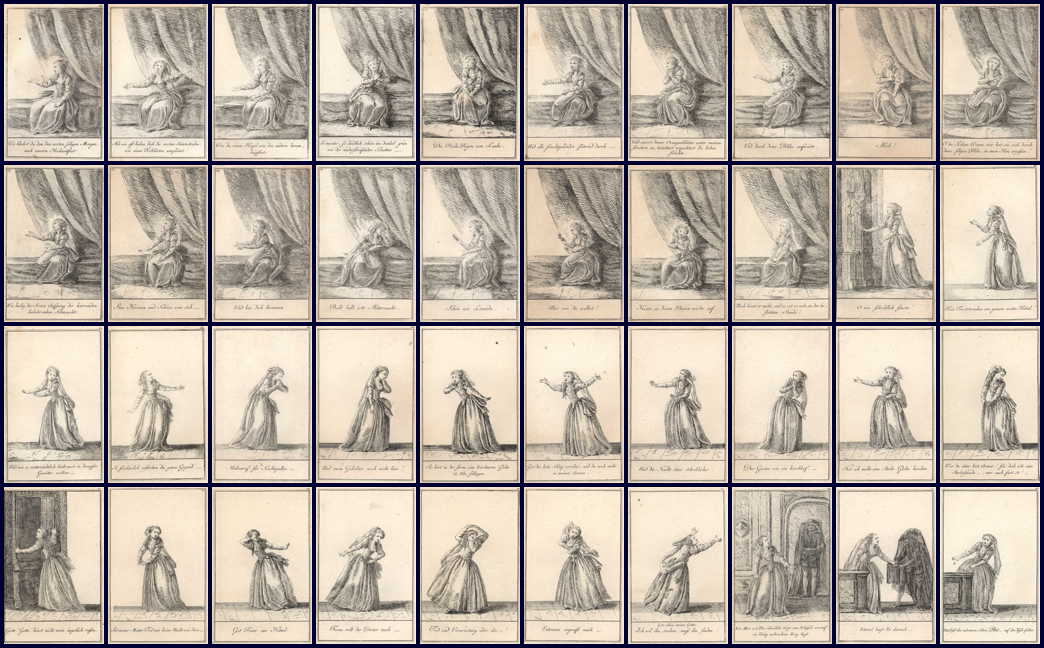

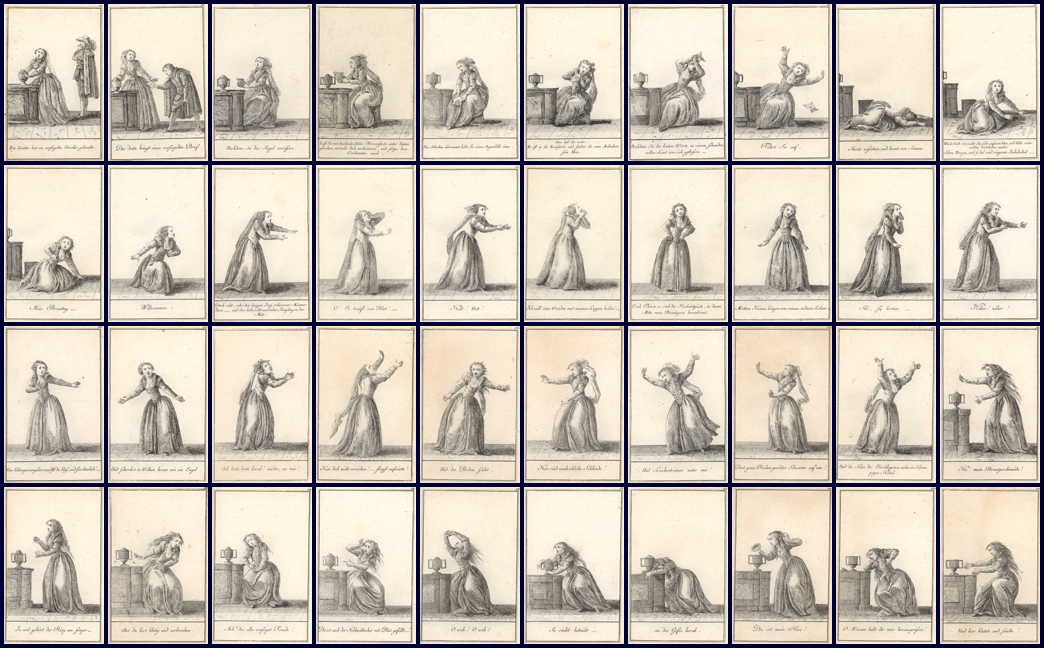

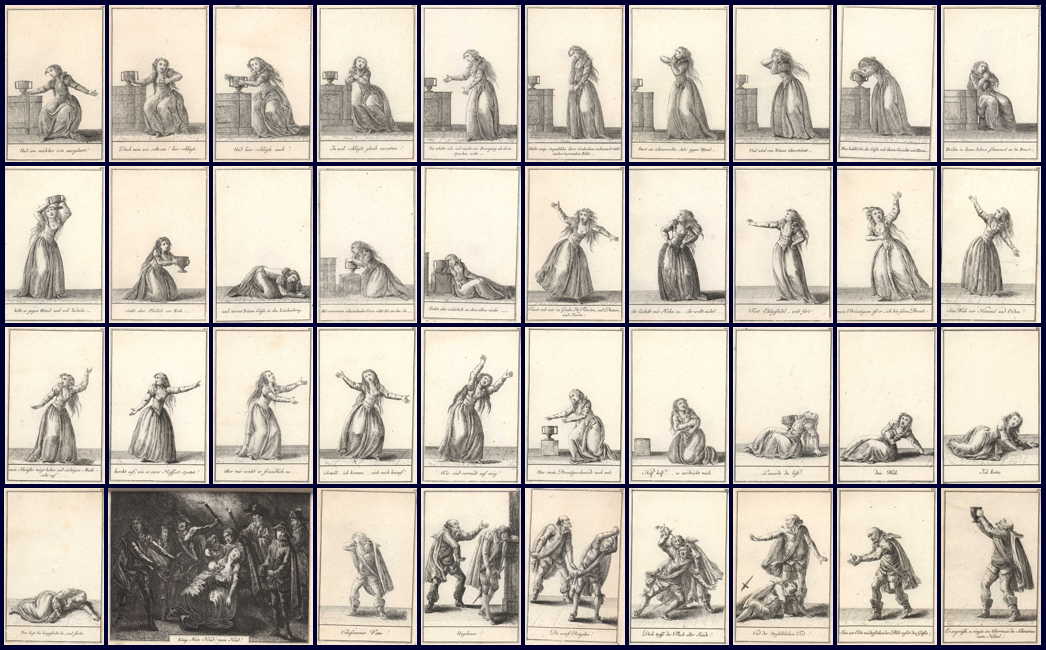

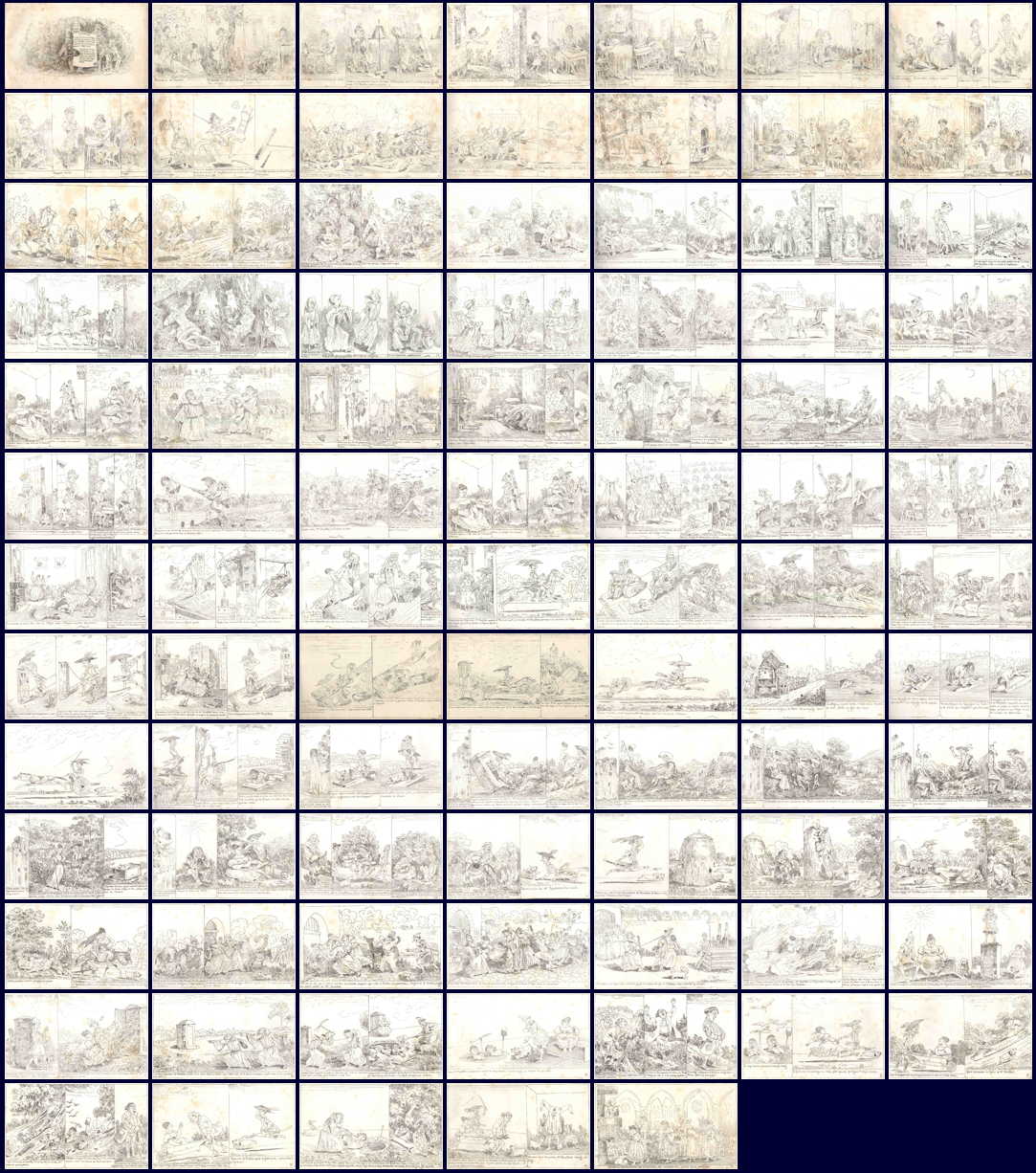

Franz Joseph Goez 'Lenardo und Blandine' 1783 Ironically this, the first actual graphic novel(ette), probably had little influence. It was too ahead of its time as far as the comic-structure is concerned. In content it was delightfully very much of its time, full of outrageous melodrama. Here's the complete sequence, with my translation underneath: page 1-34 page 35-65 page 66-93 page 94-125 page 126-160 All on one page     |

James Gillray - 'The Table's turned - Billy in the devil's claws / Billy sending the devil packing'

Much more influencial than Hogarth or Goez were the thousands of British political cartoons. Most were just that, cartoons, meaning single image jokes. However, a huge number of them used (and developed the use of) speechbaloons. And a good number did in fact use two or more interdependant images to tell a story. (That means they were comics.)

|

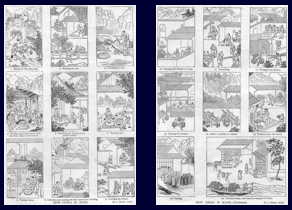

Chinese Woodcut 'How China is Made' (china = porcelain) (late 18th cent., reprinted 1893)  |

1800 - 1840 (pre-Töpffer)

|

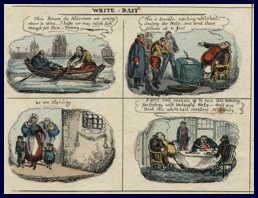

William Heath - 'White Bait' (1830)

(a four-panel comic strip with speechbaloons)  |

|

Thomas Rowlandson Part 1 - 'THE TOUR of DOCTOR SYNTAX, In search of the PICTURESQUE' This is not a comic. It's not even a sequential series of images, like a Hogarthian progress, or even illustrations of a novel. But it can be seen as a milestone in comics history, because of the influence on Rodolphe Toepffer, who imitated the type of main character, the drawing style and the general atmosphere of countryfied wackyness. The use and re-use of one striking visual character, generally recognized and popular, is certainly typical of many comics to come. |

The Birth of Modern Comics (1800-1860)

|

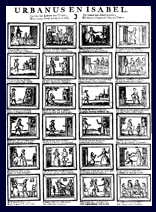

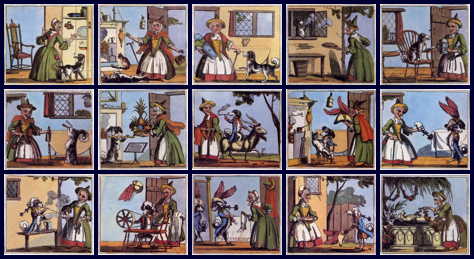

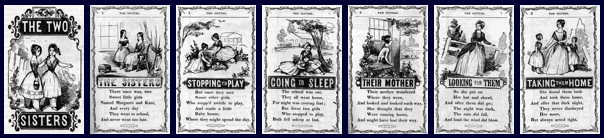

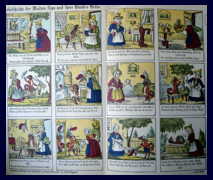

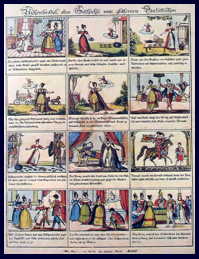

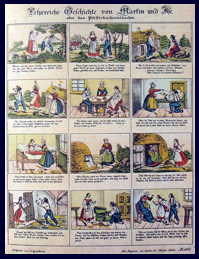

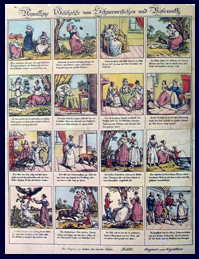

Modern comics, with a storytelling vocabulary that's still used today, were developed in America's newspaper strips, circa 1900-1920. They were mostly following a tradition of short, colourful picture-stories for children. The direct influence was the slapstick work by Wilhelm Busch and others in a similar vein. But that in turn was built on a sixty year (or more) tradition of children's comics. Busch started working in 1859, for a series of picture broadsheets called 'Münchner Bilderbogen' (See below, or click here for examples), which had been going since 1849, a series which included many inventive and sumptiously illustrated comics from the start. These were themselves influenced by the charmingly naive 'Neuruppiner Bilderbogen', which started producing comic-like picture stories in 1835. And those again were influenced by British chapbooks with comic-like picture stories, starting around 1800. Even earlier were precursors in Holland. Below are a number of examples, in case you think I'm making this all up. First two very early examples from Holland. It seems that although the Dutch had the most spectacular fall in artistic relevance around 1700, there still was an important tradition of printmaking, and highly important for the development of comics. Urbanus and Isabel Dutch Broadsheet (circa 1750) They marry. He goes off whoring. She divorces him. Years later he comes crawling back and she is overjoyed to take him back and all is well. Maybe this one wasn't a childrens story yet (although you never know with the Dutch), but the next one is.  Little Red Ridinghood Dutch Broadsheet (1800) by G. Oortmann, publisher: by de Erve H. Rynders - earliest Dutch broadsheet after Perrault. This predates the famous Grimm's version by 11 years.  From around 1800 the most important country for comics is England. Here stories told in pictures turn up inside chap-books. Chapbooks were small booklets of four, (or multiples of four: 8, 12,...) pages, and sold by itinerant merchants or chapmen (Old English: ceapman from 'ceap' - bargaining, trade) from the 16th to the early 19th century. They were illustrated with woodcuts and had stories of popular heroes, folklore, famous crimes, ballads, nursery rhymes, schooltexts (ABCs), bible tales, etc, and were the main literature beside the bible for the common man and children. They too were sometimes sold as sheets which had to be cut up and bound, DIY-fashion. Most chapbooks were not comics of course, but enough of them were to constitute a genuine and influential tradition. Some of the examples below are from American edtions. I'm not sure if these were reprints, copies or original. The Little Man & the Little Maid (1807)  The Comical Adventures of the Little Woman, Her Dog and the Pedlar (1820s) printed in Baltimore, by William Raint  Robert Branston Old Mother Hubbard and her Dog - Various early editions including a lovely one from 1819, probably by Robert Branston    Robert Branston 'The Comical Cat' (1818) Another 'Madam with an animal' thingy by Branston, plus a couple of later US variations.    Robert Branston Dame Wiggins of Lee and her Seven Wonderful Cats (1823) More an illustrated story than a comic, because not enough of the relevant action is shown visually. This was a favourite childrens book of the art critic John Ruskin.  Grandmamma Easy's Old Dame Hicket and Her Wonderful Cricket (circa 1840) Boston: Brown, Bazin & Co. Nashua, N.H.: N.P Greene & Co.  There are a lot more of these wacky old-Mother-this-Grandma-that picture books. Below examples of more conventional 19th century stories. The Two Sisters (circa 1825) From The Pretty Primer (The Juvenile Gem), Huestis & Cozans, 104 Nassau Street, New York  The Story of Little Sarah an Her Johnny-Cake (circa 1830) Boston: W.J.Reynolds & Co.  The Children in the Wood (circa 1825) published by Dunigan, New York  Adventures of Little Red Riding Hood (circa 1820) Mark's Edition - Published by Fisk & Little, 82 State-Street, Albany, New York  These chapbooks had an important influence on the next stage of mass-market comics for children. In the mid 1830s the little town of Neuruppin, north of Berlin, became an important centre for picture sheets. A good number of these were comics. Below are a few early examples. Later on, in 1848, these Neuruppiner Bilderbogen themselves influenced the more sophisticated 'Münchner Bilderbogen' (Munich picture broadsheets), where in 1859 the great Wilhelm Busch started his own brand of picture stories, which would influence cartoonists all over the world, and eventually the Sunday supplement comics. In other words, there is a direct line of influence from the Dutch broadsheets/ English chapbooks to 20th century comics. Geschichte der Madam Rips und ihres Hundes Bello 1835/40 This sheet demonstrates the international influence of British picture stories - a close copy of Old Hubbard, translated into German: (the English version was here) . Bello comes from 'bellen', to bark. Typical doggie name.

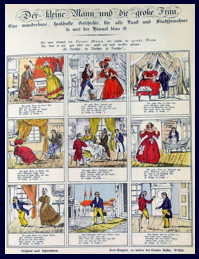

More common were these charming fairy tale adaptations: Cinderella 1835/40  Hansel and Gretel (here called Martin and Ilse) 1835/40  Erzählung vom kleinen Däumling / Story about Little Tom Thumb (1835/40)  Schneeweisschen und Rosenrot (1835/40) (Little Snowwhite and Rosered) (not the Snowwhite, who is called 'Schneewittchen' in German)  There were also popular stories of romantic robbers: Rinaldo Rinaldini (1835/40) ...  ...or a satire for grown-ups about emancipated women (and why to avoid them): Der Kleine Mann und die grosse Frau (The little Man and the large Woman) (1835/40)  Heinrich Hoffmann 'Struwwelpeter' (drawn 1844, published 1847 - English edition 1848) This famous picture book is stylistically related to earlier chapbooks and Bilderbogen / picture broad sheets. The hunter/rabbit story is similar to a panel from an earlier Bilderbogen showing (non-sequential) instances of a 'topsy turvy' world.  |

Rodolphe Töpffer

1840 - 1860 (pre-Busch)

Early Comics in Print

If you have questions about early comics, please direct them to this mailing list: Platinum Age Comics

Copyright © 2011 by Andy Konky Kru

Home Early Comics Links Abstract Comics Other Comics Konky Kru

|

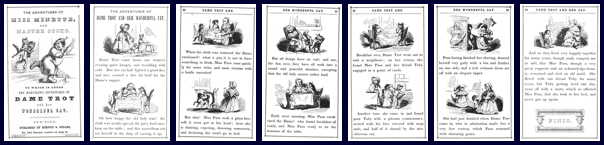

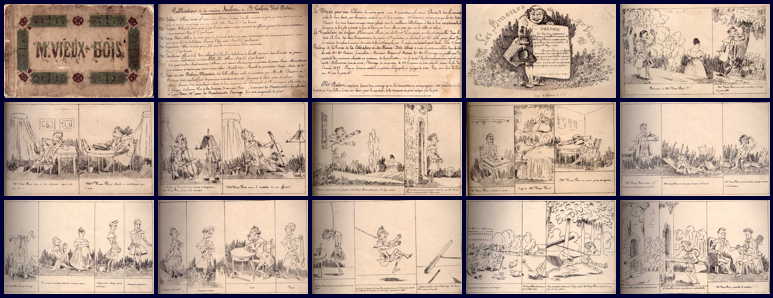

Index Monsieur Vieuxbois (1839) (partial translation) the same, but with smaller pictures - click here  Comparison of the Aubert Pirate Version (1839) and the US copy (1842)   Comparison of Monsieur Tric Trac and a Dutch sequel (Prikkebeen)  Comparison of Vieuxbois and Cruikshank  EXTERNAL LINK: 'Histoire de Mr. Vieux Bois' Original manuscript version of Monsieur Vieuxbois, 1827 (30 pages/158 panels) with text typed out underneath, and a translation. The first printed edition was published ten years later, expanded to 88 pages/198 panels. The second edition 1839 (as presented above on my own site) had 92 pages / 220 panels. |

1840 - 1860 (pre-Busch)

|

Alfred Crowquill (Alfred Henry Forrester) 'Pantomime, to be played at home' 1849  |

|

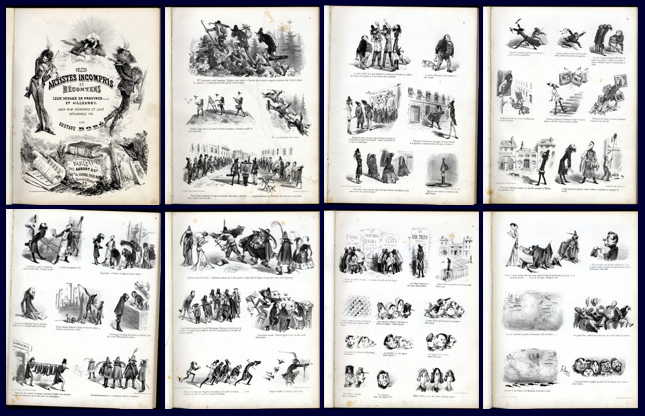

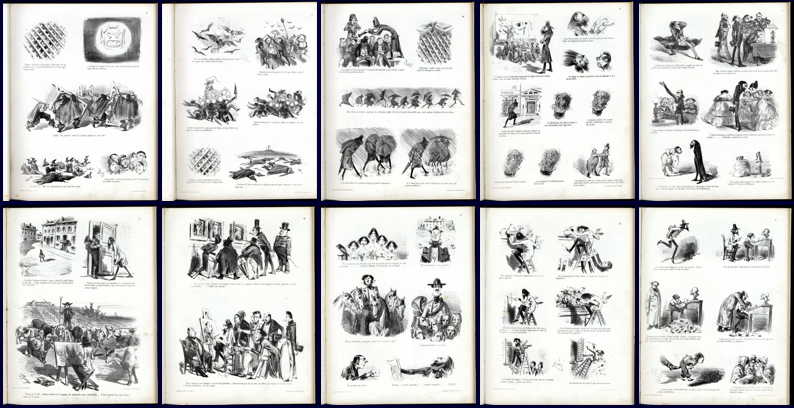

Gustave Doré 'Trois artistes incompris et mecontens' (1858) - Outstanding lithos by his own hand part 1  part 2  part 3  |

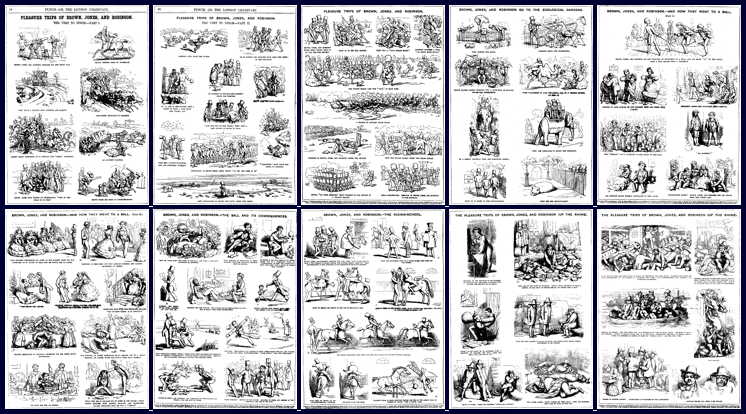

Richard Doyle- Pleasure Trips of Brown, Jones and Robertson - from Punch, 1850  |

Grandville - A dream of crime and punishment, Gertrude (1847) |

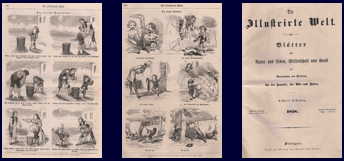

Anonymous - Two comics from the magazine 'Die Illustrierte Welt' Stuttgart (1858) (sechster Jahrgang)

|

Pages from the magazine 'Leuchtkugeln' 1848 |

Timolˇon Marie Lobrichon Histoire de Mr. Tuberculus (1856) (only a few pages) |

|

John Tenniel (the illustrator of Alice in Wonderland, 1864) How Mr. Peter Piper Enjoyed a Day's 'Pig-sticking' 1853  How Mr. Peter Piper Tried his Hand at Buffalo-shooting 1853  How Mr. Peter Piper Was Induced to Join in a Bear-hunt 1853  How Mr. Peter Piper Accepted an Invitation from the Rajah of R. to Hunt a 'Royal Bengal Tiger' 1853  Mr. Piper (all on one page)

|

Early Comics in Print

If you have questions about early comics, please direct them to this mailing list: Platinum Age Comics

Copyright © 2011 by Andy Konky Kru

Home Early Comics Links Abstract Comics Other Comics Konky Kru